|

| James Austin Sylvester, as an old man |

In one of the more obscure, but authentic accounts of the Texas

Revolution, that of Creed Taylor,[1] is a story of incredible heroism in the battle of Béxar. Creed’s account, taken down decades after the

revolution, was published in a small book, “Tall Men With Long Rifles,” which

can be found here.[2] In his description of the battle in which Texian forces first captured San Antonio in December 1835, Taylor describes the troops led by Col. Ben Milam fighting their way into the city, house-by-house, sometimes rushing from one building to another, at other times, hacking

their way through adjoining adobe walls of one house to seize another.

|

| Creed Taylor's Account of the Texas Revolution |

“Of daring and heroic deeds occurring during the assault, a volume could be written – every man fought for himself and everyone proved himself a hero. On the third day, after we had captured the house on the north side of the plaza, the Mexicans planted a cannon to the left, just outside their main works and trained it on the building we had just taken. This gun was playing havoc with our shelter. Seeing this, a young man from Nacogdoches, by the name of Sylvester, of Captain Edward’s company, made a dash for the gun, shot one of the gunners, knocked another down with his rifle, spiked the cannon, and escaped back to the lines. Cheer after cheer went up from his comrades, and Ben Milam declared it the bravest deed he had ever seen or read about.”

“Cheer after cheer went up from his comrades, and Ben Milam declared it the bravest deed he had ever seen or read about.”

The account is confirmed in a separate report from another

witness, Stephen F. Sparks:

“When we had taken the north row of houses and were firing on

the outside of the doors and windows, Sylvester ran across the Plaza, right

through the Mexicans, and spiked their cannon, then turn and ran back; just as

he jumped in a door, he turned to look, and as he did so, he had one of his

eyes shot out.[3]

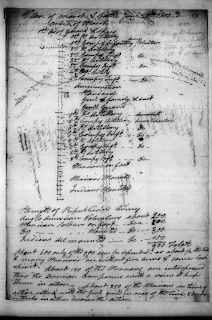

Reading these accounts – both of which mention the man named Sylvester, with no further identification – I decided I had to track this person down. Looking for clues in this book, I noted that elsewhere in his account, Creed Taylor mentions a “Jim Sylvester,” but he doesn’t clarify that this is the same person. But confirmation comes from the Muster Rolls of the Texian Army. In the rolls of the 1st Regiment of Texan Volunteers for December 1835 – the time of the battle – there is a J.N. Sylvester, a sergeant. Yet no such person appears anywhere else. A look at a later date of the same muster rolls confirms his name: James A. Sylvester. As is frequently the case, a letter is often mis-transcribed when an account is converted from handwriting to print. “J.N. Sylvester” was certainly “J.A. Sylvester,” confirmed by his exactly identical position within the unit hierarchy.

So who was James A. Sylvester? As far as I know, mine is the first confirmation that he was the man who performed the heroics at Béxar, but he’s actually very well known for two other events, to which we will get in a moment. But no account of Sylvester’s later exploits, has ever connected him to these early heroics in Béxar.James A. Sylvester was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1807

and worked as an apprentice printer in Kentucky, before making his way to Texas

and settling in Nacogdoches.[4] We don’t know when he joined

in the Texian Army, but it was likely after the Battle of Gonzales, as many men

flocked to join the army that was marching on San Antonio. Spark’s account of Sylvester’s

eye being “shot out” suggests a shocking – possibly fatal wound, but it clearly

wasn’t. In fact, it was likely the wound that saved his life, because Sylvester

would likely have been taken to Gonzales to recover and would therefore miss

his chance of martyrdom at the Alamo in March 1836.

By mid March, 1836, Sylvester, presumably having recovered

from his wound, was made second sergeant and color bearer of Captain Sidney

Sherman’s Volunteers. With the rest of the company, Sylvester would march Eastward

with Sam Houston’s army. According to one account, he was actually captured by

Mexican soldiers at Harrisburg, but he managed to escape, rejoining the Texian

army just in time for the fateful Battle of San Jacinto.

Sylvester, who had been fighting since Béxar as a volunteer,

appears to have also been granted a commission as Captain in the regular Texian

army, but he didn’t take advantage of it, and chose to continue as a sergeant

of volunteers. As flag bearer, he had a distinct privilege, for his unit,

Sherman’s volunteers, carried a large flag featuring a Goddess of Liberty, presented

to the unit by the ladies of Newport, Kentucky. It was the only flag known to

have been flown during the battle. James Sylvester carried that it throughout

the 18 minute fight, and is therefore immortalized in the famous painting of

the battle by Henry McArdle.

|

| Henry McArdle's Painting of the Battle of San Jacinto Below: A close up of the flag. Although the image leaves the flag bearer mysteriously vague, we know that person was James Sylvester. |

But there’s more to the story, because James Sylvester the heroic fighter at Béxar, the standard bearer at San Jacinto, had one more claim to fame in store. Following the battle, General Edward Burleson organized several scouts to hunt for Mexican stragglers, of which Sylvester was one. From his own account:[5]

“The squad under my command proceeded back to camp. We left

the main road and took down the bayou. We had not proceeded very far before

some one of them proposed to skirt the timber in search of game. I took the

straight direction promising to await their arrival at a certain point. After

leaving the party, pursuing my course alone, I suddenly espied an object coming

towards me, near a ravine. I immediately turned and made an effort to attract

their attention. When I again looked for the object, it had vanished. Riding in

the direction in which I had seen it, I came up to the figure of something

covered with a Mexican blanket…

He saw that it was a man in hiding. Sylvester came up on him.

“I ordered him to get up, which he did, very reluctantly and immediately took hold of my hand and kissed it several times, and asked for General Houston and seemed very solicitious to find out whether he had been killed in the battle the day previous. I replied assuring him that General Houston was only wounded, and was then in his camp. I then asked him who he was when he replied that he was nothing but a common soldier---I remarked the fineness of his shirt bosom---which he tried to conceal and told him he was no common soldier; if so he must be a thief. He seemed much disconcerted, but finally stated that he was an aide to General Lopez de Santa Anna---To affirm his assertion, he drew from his pocket an official note from General Urrea to General Santa Anna dated on the Brazos informing Santa Anna that he would be able to form a junction at or near Galveston and should immediately take up line of march to Velasco.”

Sylvester initially bought the story, figuring that an aide would indeed be likely to have such a paper. As his squad rode up to join him, Sylvester prepared to head back. The “soldier” he had captured complained of fatigue and asked to ride part of the way. One of the party agreed to let him, and put him on his horse, the Texian walking for a time. When they approached the Texian camp, the officer demanded his horse back from the prisoner, who refused. Sylvester instructed him to comply, which he reluctantly did. The came into the Texian camp and Sylvester left his prisoner with the camp guard. What followed next was a famous event in Texas history: The prisoner, brought in among the Mexican captives, was welcomed with shouts of “El Presidente!” and suddenly the Texians realized that Sylvester had captured the President of Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. The Mexican dictator was then brought before Houston, who in a famous gesture of humanity, agreed to spare his life in exchange for signing the treaty that gave Texas its independence. With Santa Anna agreeing, Houston sent for Sylvester.

“When I returned to camp (having been sent for by General Houston) I was ordered to report to headquarters in person. I proceeded to the place---a wide spreading oak---and on presenting myself to General Houston, General Santa Anna immediately arose and came forward, embraced me, and turning to General Houston and other officers returned me thanks for my kindness while escorting him to camp and told me I was his savior.”

|

| The Surrender of Santa Anna |

“After an interminable length of time, Price hurried around the bend in the street. I strained my eyes to see if the others followed, and my throat tightened as I saw Sylvester, then Kegans, and finally Hodge round the bend, kneeling and firing as they came. The group paused a few minutes and exchanged fire with some Mexicans in the street behind them, then I saw them relax, laugh with each other and almost as one, turn and look in my direction. As the four grinning faces hurried toward me I realized their official objective had been to take the intersection from the enemy, but they had added and unofficial objective of their own, to rescue me as soon as possible. Now, I began to understand very faintly the spirit of the Texans which set them apart from the rest of the people the world over.”[6]

After the battle, Somervell, the commander, decided to

return to Texas, but 2/3 of his army refused, and instead continued their

invasion into Texas. Sylvester, who by this time didn’t need to prove his

courage to anyone, returned with his commander. It was fortunate too, as the

Texians who continued were ultimately captured at Mier, imprisoned and forced

to endure the brutal decimation of the infamous Black Bean Affair, in

which one in ten of their number were executed, and the remainder sent to

Mexico in irons. Sylvester eventually moved to Louisiana, served as editor of a

newspaper there, and died in 1882.

[1]

Creed Taylor is the son of Josiah Taylor, one of the key commanders in the 1813

Republican Army of the North, the subject of my book, “The Lost War for Texas:

Mexican Rebels, American Burrites and the Texas Revolution of 1811.” www.lostwarfortexas.com

[2]

James T. DeShields, “Tall Men With Long Rifles: The Glamourous Story of the

Texas Revolution as Told By Captain Creed Taylor, Who Fought in that Heroic

Struggle from Gonzales to San Jacinto,” San Antonio, Tx: The Naylor Company, 1935.

[3]

Texas State Historical Association. The Quarterly of the Texas State

Historical Association, Volume 12, July 1908 - April, 1909, periodical, 1909; Austin,

Texas. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth101048/: accessed

May 16, 2025), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas

History, https://texashistory.unt.edu;

crediting Texas State Historical Association, pg. 62.

[4]

Sylvester’s Handbook of Texas entry suggests he came to Texas as part of Sidney

Sherman’s company of Kentucky Riflemen, but this is likely in error, as Sherman’s

company didn’t even arrive in Texas until February 1836, whereas the muster

rolls of the army clearly show Sylvester was present at the Siege of Béxar.

Also, Creed Taylor’s account clearly implies that Sylvester was from Nacogdoches,

not merely an outsider passing through. It’s hard to know for sure, because in Texas

at this time, residence of merely a few months or even weeks could count in the

eyes of one’s neighbors.

[5]

This account is taken from the Sons of Dewitt Colony webpage. It is a great

source, but maddingly, doesn’t provide its own sources. Thus while I have a

good idea of where the original account can likely be found, I have not been able to do so due to limitations of Internet resources.

[6] This account comes from a book called “I Went to Mier” published shortly after the incidents by Hartman. The book is extremely rare and I have not been able to locate it, but it is quoted in two sources, in Katie Barnard, “Old Texians” The Texas Historian, Vol. 38, No. 3, January 1978, 12; and in a book called “A Man Called Jim” by Anemone Love Binkley, which is further excerpted in a genealogical article about John Ross Kegans, one of the men involved, which can be found here: https://www.browncountytexasgenealogy.com/Articles/KegansMEIR.pdf