The Republican Army of the North, the force which invaded Texas in August 1812, was an army always in flux. For this reason, pinning down the army's strength is a very difficult thing.

The original filibuster core of the force, which crossed the border and captured Nacogdoches on August 11, was only about 150 men. But the army soon began adding new recruits, both from additional filibusters arriving from Louisiana and native Tejanos and Indians who joined. Following the epic siege of La Bahia, the army defeated the Spanish royalists at Rosillo and captured San Antonio. Then, following the execution of 11 Spanish royalist officers by vengeful natives, large numbers of Anglo Americans went home. Some left, never return. Others, like Samuel Kemper, took furloughs and returned to fight later on.

Even while this was happening, new recruits were always coming to Texas and replacing old fighters, or even augmenting them. Thus, the strength seems to have always been uncertain. But there are some datapoints that can be considered in piecing together the army strength.

Invasion of Texas, August 1812: 130-150 men.[1] The army’s agents in Natchitoches claimed an additional 500-600 men were on the way to join them. Spanish Commander Bernardino Montero learned on July 27 from a French creole that there were 365 Americans on the other side. This number was likely inflated, though the smaller (150) number may have been merely an advanced force which penetrated Texas, and these follow-on troops, whatever the number, likely followed in their wake.[2]

Other Spanish sources suggest from 2,000-3,000 men were to join. These modest and fanciful numbers, respectively, were likely projections of hoped-for strength, not reality. In any event, the proclamation of Gov. William C.C. Claiborne on August 11 outlawing the affair, may have deterred many of these.

Nacogdoches: September, 1812: 240 men. Whatever the numbers which turned back after the proclamation, significant numbers, possibly several hundred, continued on, but took time to augment the force. Around this time, William Shaler, a close observer, estimated the total number of Americans at 240. This includes the first Tejano/Mexican contingents of the army began to be formed in Nacogdoches. These were likely small as some soldiers chose to “serve” in their hometown. The total number who joined the army itself (mostly Spanish deserters) was probably only around 50.[3]

Trinidad de Salcedo, October 1812: 450-500 men. This is where the numbers get confusing. William Shaler would say he didn’t know how many men were in the republican force within 300 men! But this appears to be the time that the bulk of the follow-on recruits arrived, although they appear to have trickled in rather than arrived in large masses. The percentage was likely around 3 Anglos to every 1 Mexican. The army had at least three four pounder cannon and one other of unknown size.[4]

La Bahía, November 1812-Febuary 1813: 450-800 men. At La Bahía, the army occupied the presidio and was then besieged. The numbers of fighters swayed somewhat, with the additions and subtractions being almost entirely from local Tejanos or captured royalists. Some deserted to and from the republicans, making the nature of this change impossible to determine.

Battle of Rosillo, March 29, 1813: 400-800 men. After the Siege of La Bahía was lifted, Reuben Ross and James Gaines arrived with additional reinforcements of Anglo-Americans and Indians, respectively. Gaines places the number at about 600, and another member of the army gave the same number. Other sources suggest a higher number, but these may include troops not classified as “effective” – including, for example, wounded or sick. Coming off a siege of nearly four months, it would be understandable if large numbers were ill. Additionally, more Mexican residents of La Bahía likely joined them, along with a small number of citizens of San Antonio, who had filtered past the retreating Spaniards. As for the Spanish numbers they faced, Hall places it at 2,500, which is virtually impossible, given the available manpower. The number is likely slightly in excess of the Republican numbers, possibly 1,000-1,500.[5]

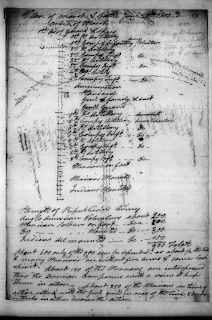

San Antonio, April 9, 1813: Approximately 650-700 men. This is the only “good” datapoint we have on the army, courtesy of a document recently discovered in the US National Archives. This is the only known muster roll of the army, not including names, but aggregates named by company. The total, which includes Anglo-Americans only, is 439. This shows remarkable consistency with some of the numbers in previous accounts, and extrapolating Mexicans and Indians from those, we get around 650-700 men. This is about the time of the desertions caused by the massacre of the Spanish royalists, but most evidence points to those desertions being made good if not augmented, by new arrivals.

Battle of Alazán, June 20, 1813: 900 men. This is another key, good datapoint, from the Alazán order of march document also discovered in the National Archives. This lists 250 Anglo-Americans - a significant drop in the forces from the April 9 document. This likely represents the desertions having finally run their course, but also likely does not include the sick, which the April 9 document does. What we do see is a significant growth in the Mexican/Tejano contingent, to around 200 on foot and 300 mounted. Around 150 Indians are counted, rounding out the number. This represents the turning point in which the army finally has a majority native Mexican contingent, though the leadership in the field is still Anglo-American. However, this comes with a caveat. As the document states, "About 600 only of the 900 can be depended [on] as about 1/2 of the Indians and many Mexicans are without firearms & some lack spirit."

Battle of Medina, August 18, 1813: 1,500-1,800. The numbers of the Republican Army of the North at the Battle of Medina are, like most other numbers, uncertain. But we can make an educated guess.

Subsequent republican sources give the following size of the army: Joseph Wilkinson, 1,200; Bullard, 1,500 and Beltrán, 1,800 (consisting of 1,000 Mexicans and 800 Americans). After the battle, Kemper and Toledo told an American newspaper editor that there were about 450 Americans and between 600-700 Mexicans, for just under 1,000 (almost certainly downplayed). The source for Kemper and Toledo’s numbers is the following article: “We have No further Particulars of the affair of the 18th ult. near San Antonio…” Daily National Intelligencer, October 18, 1813. Joseph Wilkinson to Shaler, June 25, 1813. CSA. [Bullard] “A Visit to Texas.” Hunter, “The Battle of Medina,” 10.

There are two documents, both captured by Arredondo, which outline the Republican Army’s order of battle. The first is a letter from Guadiana to Henry Perry on August 5 and the second is Guadiana’s order of march on August 13. The former lays out Perry’s regiment, which consists of the Washington and Madison Battalions. Each has 4 companies of 126 men, giving the regimental strength as 8 companies and 504 men (including staff). There is additionally a second American regiment, which will be placed under Kemper. Notably, the size of Kemper’s regiment is not given, nor is its structure.

If the two American regiments were equal in size (2 battalions of 4 companies each) and the battalions at full strength, that would give the Anglo contingent alone over 1,000 men, not even counting artillerists. As this is nearly four times the size of the Anglo force at Alazán and twice Shaler’s estimate, it is certainly inflated. Multiple sources suggest that Toledo inherited an army that was ethnically mixed and then broke them into separate divisions, and one is tempted to suspect this is the source of the large number of 1,000 in the Perry letter, for if the Mexican contingent was within the regimental structure on April 5, but separated from it before April 13, that would account for the high number. Yet the Alazán order of battle document shows that the army was already operating in separate contingents in that earlier battle. All sources suggest the Mexican troops outnumbered the Anglos at the Battle of Medina. Given 1,000 Anglos, the army would have to be 2,200-2,500 men, far above any republican estimate.

The order of march document, additionally, suggests that the names “Washington” and “Madison” denote not two battalions within one regiment, but separate regiments themselves. This document also clearly shows the Mexican contingent as separate, since they march between the Washington and Madison regiments or battalions. But this later document gives no numbers for any contingent.

There is an interpretation that this author feels accounts for both the naming discrepancy and what appears to be the inflated size of the army that the two-regiment structure suggests. When Guadiana wrote his letter to Perry on August 5, shortly after Toledo’s arrival, Samuel Kemper had not yet returned from the United States. His regiment, undescribed in the letter, was to be led in the interim by a Sergeant Major (who was probably Josiah Taylor given his later role). Guadiana expected that Kemper would bring a significant reinforcement along with him.

This, and perhaps a small contingent already awaiting him under Taylor, would stand up the second regiment. This is given credence by the fact that the 8 companies (4 per battalion) reflected in the Perry regiment alone exactly mirrors the 8 companies at Alazán. Thus, Perry’s regiment likely was the bulk of the veteran army, and Kemper’s regiment in waiting a mere skeleton force to be filled out by reinforcements.

But, as Beltrán wrote, “Toledo expected to leave the Sabine with an army of at least 2,000 men…but in this, he was sorely disappointed.” Whatever men Kemper brought with him were much smaller than needed. Had Kemper’s reinforcement been more than 200, the sources undoubtably would have recalled its arrival, but it passed unremarked upon.

It seems likely that after Kemper’s arrival with a smaller force, this fanciful structure was then altered, and the Washington and Madison battalions themselves became regiments, suggesting the final number was something close to the 504 listed in the August 5 document, plus Kemper’s reinforcement and whatever other troops were available. These were then all effectively placed under the command of Kemper, with possibly one regiment under Perry the other one under Taylor.

Historically, the Anglo contingent had been 422 before the desertions caused by the execution of the Royalists, then 250 at Alazán. It had likely grown to 500-600 by August 5. Thus, the likely Anglo contingent was probably in the 600-800 range when all is said and done. Adding in a very plausible Mexican contingent of 1,000, this puts the numbers in line with Bullard and Beltrán’s estimates (1,500/1,800). This then is the structure and numbers this author assumes in the book.

[1] Sibley to Eustis, August 5, 1812 in Garrett, “Dr. John Sibley,” Vol. 49, No. 3.

[2] Bernardino Montero to Manuel Salcedo, July 23, 1813. “Texas History Research, Neutral Territory” Folder, Karle Wilson Baker Papers, Ralph W. Steen Library, Stephen F. Austin State University.

[3] Shaler to Monroe, August 18, 1812, Shaler Letterbooks. Henry P. Walker, “William McLane’s Narrative,” Vol. 66, No. 2 (Oct. 1962), 243. Baker, 224-9. Henry P. Walker, “William McLane’s Narrative,” SWHQ, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Oct. 1962), 243-5. RBB Vol.70: 244.

[4] Hall account in Lamar papers, Gulick 4(1):279. Gulick, 6:146. Shaler to Monroe, October 1, 1812, Shaler to Monroe, October 6, 1812, Shaler to Monroe, November 10, 1812, Shaler Letterbooks.

[5] Gulick 1:45. Baker, 227. Reuben Ross to William Shaler, April 15, 1813, CSA. Gulick, 5:365. Walker, “McLane's Narrative,” 66, No. 3 (Jan. 1963), 460. “1813 Letter from Bart Fleming to Levin Wailes, Esq.,” June 7, 1813, in Gutiérrez de Lara collection, Eugene C. Barker Texas History Center, The University of Texas at Austin, cited in I. Waynne Cox, “Field Survey and Archival Research for the Rosillo Creek Battleground Area, Southeast San Antonio, Texas,” Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1990 , Article 1, available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1990/iss1/1 (accessed August 24, 2021), 3.